Race, Class, and Empire: Reading J. Sakai’s ‘Settlers’

The primarily white character of DSA is shaped by the contradictions within the class position of its base, being both wage-earning proletarians and beneficiaries of imperialist superprofits. We must reckon with the historical attachment to reformism created by this struggle.

As DSA continues to grow and grapple with its role in building a multiracial socialist movement, J. Sakai’s Settlers: The Mythology of the White Proletariat offers an incisive critique and a crucial lens for understanding the challenges of organizing within a settler society. Through our analysis of Settlers, we seek to understand the ways in which our position within a global hegemon and our history as a privileged class affect our organizing, and why and how the US working class has such a vested material interest in the racism ingrained in our history, even under the veneer of progressivism.

Racial-Class in the US

Western socialists most often work off of a basic definition of Marxist class. The proletariat, or interchangeably, the working class, consists of anyone who must sell their labor for a wage from the capitalist class to survive. But this definition is oversimplified to the point of sloganeering: it does not take into account the position the United States occupies atop a global empire, and how this affects its residents and the class dynamics within.

In Settlers, J. Sakai argues an alternate thesis: within the settler colonial United States, common working-class interests are overridden by the imperialist contradictions between oppressor and internally oppressed nations. Drawing on the frameworks of imperialism stretching back to Marx’s own writing and combining it with a New Left racial lens, Sakai presents an analysis of the complex and contradictory class position of the US’s working class that draws distinctions on the incentives and treatment of the class along racial lines.

US imperialism creates and enforces an extractivist economic relationship between the imperial core, centered on the US while also including other ally “first world” countries such as those of western Europe, and the imperial periphery, the colonies and later neocolonies of the global south. While the US capitalist class extracts profit from the exploitation of its own domestic working class, it also extracts superprofit from the working class of the rest of the world. This superprofit, money looted from the global south via unequal commodity exchange and a lack of productive parity, does not all stay in the hands of the ruling class. Instead, it is circulated through the whole domestic economy, and some parts of it are distributed to the working class of the imperial core. The particulars of this circulation and distribution, specifically the racialized differences, is where Sakai’s analysis is focused.

Distribution of superprofit takes a variety of forms. Some come in the form of social services and public goods. The redistribution of imperial superprofits forms the backbone of European social democracies, providing financing to their much-lauded social programs. Others come in the form of higher wages, a greater personal debt ceiling, and increased standards of living. With excess money from the spoils of imperialism, capitalists are able to raise wages beyond the minimum needed to sustain the life of a worker without endangering their margins (though this is not always the case in times of crisis: see the collapse of the “middle class”). This creates a new dimension of class distinction exclusively within the imperial core: that of the imperialist beneficiary, who receives superprofits, and thereby benefits from imperialism—and has something to lose if it ends.

Sakai designates this stratum of American workers, those imperialist beneficiaries who directly receive their benefits in the form of increased wages, as labor aristocrats. This segment of the population, he argues, through social bribery, has some investment in the capitalist system, as they both receive a material benefit and have the worst edges of capitalism’s repression against them blunted. (This is more expansive than the more contemporary use of the phrase labor aristocrat that focuses more exclusively on a strata of labor bureaucracy, i.e., a union leader not truly seeking the best for his constituents.)

These benefits of imperialism that Sakai traces are not parceled out equally. Since its creation as a settler colony centuries ago, the United States has constructed and enforced a caste system for designating who should be an imperialist beneficiary, an ally to the ruling class, and who should not. The system they use is race.

Consider: a undocumented migrant from Mexico working on a farm in California may benefit from slightly higher wages as compared to before immigrating, but is reminded constantly of their class position by subminimum wages, harassment from the police and border patrol, and exclusion from citizenship. Compare this to a white, American-born, well-subsidized Midwestern farmer, who has nothing to fear from the capitalist state, and enjoys a far higher access to credit for equipment, the social possibility of renting fields for their own work from larger farmers, etc. Both are working class, both are in the same industry, and yet their class positions, their relationship to capitalism, imperialism, and the capitalist state, differ.

These economically-enforced racial divisions form the basis of racial-class, where racial antagonism is embedded in the social relations of our class system. Whiteness, then, is used to distinguish those who sit at the top of this hierarchy—those who should be imperialist beneficiaries and share in the spoils of the American empire, those who may be drawn upon to form the labor aristocracy, and those who therefore have the most to gain by supporting capitalism. The ability to take advantage of the circulation of imperial superprofits, to include oneself in their distribution, plays a role in determining one’s class position even within the “working class” distinction.

This does not mean that white Americans cannot be working class; nor that we should accept a defeatist Third Worldist position that finds no hope in organizing the working class in the imperial core. Rather, it means there is a contradiction between multiple aspects of US class position—between that of an exploited wage-earning proletarian, and that of a recipient of superprofits, the incentive system of imperialism.

Within the United States, the organization of the working class must reckon with both the recipient and non-recipient aspects of the class, as well as its historical impacts on class and racial solidarity within the class. A core and often missed message of this criticism is that racial antagonism around these kinds of broader social inequalities—particularly around real property, racial integration, and the broad social benefits of the middle-class—is central to preventing multiracial class solidarity.

When Reformism Works

Reforms within US imperial capitalism, at their core, are a redirection of a portion of capitalist profit toward a section of the working class. When we campaign for a Green New Deal, we are not asking for an end to imperial superprofits or a transformation of the Western-bent supply chain that builds the new power production—instead, we ask merely that once profit has been extracted from the global south and brought to the US, that it be used to benefit us. When we form a union at a multinational company and demand higher wages, we are not asking that company to stop earning money from global exploitation, but instead asking that more of that money go to us.

This type of more-for-me organizing forms the basis of reformism. For a stratum of white, middle-class Americans who form the pool from which the labor aristocracy is drawn, the opportunity to demand these changes and move toward the ranks of privileged imperialist beneficiaries is more readily available.

The “New Deal” is arguably the largest example of such a reformist project domestically. Often celebrated as a successful case of progressive triumph, the New Deal was, in reality, a bourgeois project designed to preserve the capitalist system, or “deal” both the proletariat and bourgeoisie a new hand in the face of crisis. The New Deal served as a strategic maneuver to co-opt working class struggle and stabilize a crisis-ridden capitalist economy on new terms, all while retaining the basic foundations of the settler-colonial project and securing its future operation. As Sakai argues, the American working class has historically been divided along racial lines, and the New Deal perpetuated this settler-colonial logic by excluding agricultural and domestic workers—disproportionately black and brown workers—from its protections, while extending concessions to the white working class to secure their loyalty to the capitalist state. The New Deal strengthened the alliance between the settler working class and the bourgeoisie, ensuring the continued oppression of colonized peoples and the global proletariat. In this light, the reformist nature of the New Deal did not radically redistribute power away from the capitalist class or give the working class some more secure base to fight from, but instead reified a reactionary consolidation of settler-capitalist power.

The Green New Deal, much like its predecessor, falls into this same reformist trap that fails to attack the roots of capitalist exploitation and settler-colonial oppression. The Green New Deal (GND) Campaign’s emphasis on winning “nonreformist reforms” and building state capacity through electoral and legislative campaigns reinforces the settler-colonial state apparatus by enshrining class access to state direction of profits rather than doing the work to dismantle the racialized value chain. The GND campaign, even when framed as “ecosocialist”, fails to confront the racialized and colonial foundations of capitalist accumulation, instead prioritizing the health of the extractivist economic arrangement itself and a renegotiation of its ends.

The internationalist framing of the GND campaign’s strategy as highlighted in their Theory of Power remains abstract and subordinate to the primary focus of imperialist exploitation. True internationalism requires not just solidarity with global struggles, but also a reckoning with the role of the US as the leading imperialist power and a settler-colonial project. The GND campaign claims to “contest” the green capitalist transition but falls short in offering a revolutionary alternative with a clear commitment to dismantling the settler-colonial and American imperialist projects. Until these tactics explicitly center on the rejection of reforming the capitalist state, they will remain complicit in perpetuating the very systems they seek to replace when only their “pragmatic” ends are implemented.

We find similar problems in the reformist approach to labor organizing. Sakai lays out a sprawling history of the US labor movement from its nascent days, arguing that labor has historically not only been compatible with racism, but that exclusionary unions have been used as a weapon toward the exclusion of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) people from jobs of a higher social caste with higher wages. This story from “New Orleans Dockworkers: Race, Labor, and Unionism, 1892-1923” supports the criticisms Sakai makes about the divisions in the American labor movement: a general strike in New Orleans where a Whites-Only union and a Black union of dock workers engaged in a strike against their working conditions and wages. The white union inevitably turned on the Black union, and then ended the strike along racial lines, explicitly for not wanting social equality for their Black co-workers. The racial-antagonisms won out over solidarity, as they have time and time again. A movement that ground one of the most important trade ports in the country to a halt failed due to racial antagonisms being prioritized over class solidarity.

Far from advancing proletarian interests, historical labor victories and struggles have served often to reinforce the divide in the working class along racial and national lines. Even more explicitly socialist unions like the IWW fell short of being genuinely anti-US or anti-imperialist, having to cater to the sensibilities of their white members lest they lose support. This failure meant that the IWW’s radicalism remained limited, unable to fully break from the settler logic that underpins the US empire, unable to cater to both the settler class’s interest and the interests of the colonized proletariat.

Instead, we see even the most radical unions ultimately being limited to reformism, needing to prioritize the ability to win economistic reforms in the interests of their members. While some would consider this a development past the racial antagonisms of the past, they largely maintain the antagonisms of imperialist social relations, and are necessarily shut out of the political realm. Sakai isn’t alone here—Lenin similarly criticizes the narrow potential of economistic struggle in What is to be Done:

The “economic struggle against the employers and the government” does not at all require an all-Russia centralized organization, and hence this struggle can never give rise to such an organization as will combine, in one general assault, all the manifestations of political opposition, protest, and indignation, an organization that will consist of professional revolutionaries and be led by the real political leaders of the entire people.

DSA’s labor strategy often falls into the trap of tailing these economistic interests. Even while unions like UAW vocally support increased tariffs in the name of improving life for American workers, DSA members argue we mustn’t alienate the average worker or the unions that represent them, or at worst, echo similar talking points about the primacy of protecting the American worker. While chasing the approval of this average worker, we must necessarily subordinate the long-term socialist horizon, and fail to confront our place within the imperialist system.

There is a reason the white US left has always fetishized the social-democratic projects of Western Europe. Here is a project they can see themselves in, the most extreme example of social bribery, a political project defined by granting its small enclaves of citizens economic security, high standards of living, and an extensive social safety net. European social democracy has consistently failed to challenge the imperialist and colonial structures that sustain global capitalism. The US socialists that valorize these projects fail to analyze or understand their reliance on imperialism and the profit it brings to support its white citizens, or connect this with its acceptance and integration of the global racial-class system that perpetuates their own flavor of racism to keep non-whites away from their imperialist spoils.

This alignment reflects a broader inability to develop a revolutionary politics that addresses the material conditions and struggles of oppressed peoples, instead clinging to strategies that ultimately uphold the status quo. Instead, they turn their derision toward the imperfect people’s revolutions of the global south—the communist projects of Asia, the pink tide governments of Latin America, the decolonial movements of Africa and the Middle East, refusing to learn from alternate political models outside of those supported by imperialism, condemning their noncompliance and regurgitating propaganda wholesale.

For segments of the working class that are more able to redirect superprofit toward themselves, reformism is a viable path toward improving one’s life in the short term. This is most starkly the case for white Americans. But embracing the ability to win reforms as a satisfactory goal necessarily means the abandonment or postponement of the destruction of capitalism, and the abandonment of all those not inside the small circle of beneficiaries that whiteness designates. We cannot claim anything so simple as the white working class being “tricked” into racism completely against their own interests—rather, it comes from an understanding of and identification with a part of their class position, and its associated interests. As Marxist-Leninists in the US, we understand that the socialist project here must practically work toward the liberation of the oppressed under US imperialism. A truly socialist project in a settler state cannot be built without first completely dismantling the property relations that it is founded on.

DSA’s Reformist Addiction

So what about DSA? What is the class composition, and therefore the class interest, of our organization? DSA’s base, the class from which we emerged and from which we continue to primarily recruit, has always been the privileged strata of America’s white middle class.

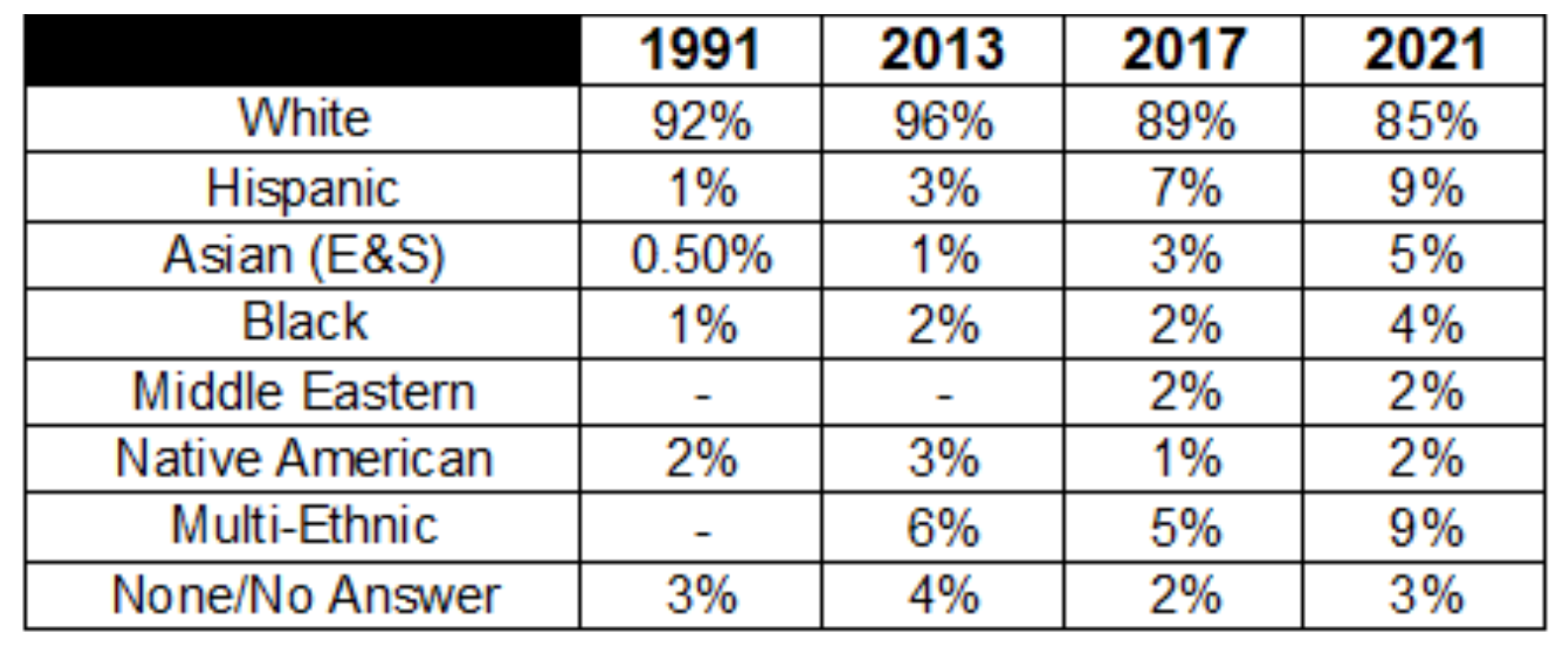

As of DSA’s 2021 organization-wide survey, 85% of DSA members listed “white” as a racial identity. This includes 77% of members who listed white as their only racial identity.

DSA’s politics reflect its class composition. As the white middle class are the primary beneficiaries of reformism, they are also its primary advocates. DSA’s work focuses largely around reform campaigns, and often marginalizes or shuts out other kinds of organizing. This creates a feedback loop as members of DSA’s existing base interested in reformist-style organizing are drawn into the organization. Because this strategy is viable and attractive for DSA’s base, the organization has no reason to push beyond reformism. Organizing communities and people outside of its normal class composition is often reduced to “Those people won’t join DSA anyway,” instead of a constructive “How can we bring these people into our fold?”

This of course means that DSA fails to attract or retain members outside of our white middle-class base, as we do not cater to their interests, but instead focus mainly on the narrow class interests of our existing membership. We can see this through the allocation of organizational resources within DSA. Labor and electoral work receive the lion’s share of funding toward external organizing, as well as the indefinite designation of national “Priority Campaign," alongside our Green New Deal efforts. These are all projects geared toward winning reformist victories, the sort that appeal to DSA’s current base.

The problems we as an organization run into, those that continually lead us down this path, are with fetishizing a deracialized Working Class, an imagined monolith of a political block that has yet to be found or activated. When we try to reduce our work down to a narrow field of winning reforms to inspire this monolithic vision of a class to action, we fall short every time. This is not action for the class, it’s action for DSA as it already exists. These sorts of “bread and butter” issues are what get us energized, and fail to find purchase in the broader class, because they’re not aimed at them. Whenever DSA tries to do anything else, there’s a wave of backlash against straying from the sort of economistic demands that this imaginary deracialized (and thus, white) worker would want.

Which is a problem—this imaginary worker haunts DSA. We’re told we must constantly tail this image that lives in our collective consciousness, tailoring our messaging and actions to them. This is reinforced by so many members’ efforts following the conventional wisdom of progressive politics: we must find a majority in order to win a campaign, and appeal to the members of that majority no matter the cost. We must identify reforms that are resonant to the broadest possible audience, hoping to appeal to their existing beliefs. But this views people as static political actors, incapable of changing opinions or of being polarized against capital. This limits politics to the act of finding already-existing majorities among our already-existing base.

It's understandable that DSA might choose this approach to practicing its politics—as Sakai explicates, these reforms are the interests of the existing majority that we attempt to appeal to. But this ignores the masses of the BIPOC proletariat that sit below whiteness in our racial-class system, ignores their interests that are not already popularized in DSA, that don't show up in voter polls or in the rhetoric of progressive politicians. They are not a part of the majority we try to appeal to. The white masses dominate culture, political activity, DSA members’ own social circles. Our history shows us the way DSA has appealed to the white masses, through social bribery, personal benefit, and the Western social-democratic promise; and by accepting the racist tendencies stamped into all of us by virtue of existing in American society, not confronting them but sublimating them, and never threatening a white cultural position atop the empire, and atop our own social democratic organization.

Every time we argue we must focus on labor or electoral organizing primarily, every time we argue that focusing on identity, or abolition, or anti-imperialism would be to our detriment, we negate the possibility of our organizing—and our organization—transgressing against the racial caste system in a revolutionary manner. Time and again, when elected members’ lack of willingness to take anti-imperialist stances test DSA’s political commitments, it is seen as a distraction that threatens DSA’s precarious grasp on power rather than an indication that the issue is at the knife’s edge of struggle against white supremacy. When campaign strategists appeal to the narrow interests of the median voter or organize around the lowest common denominator issues, they miss the opportunity to polarize people against the contradictions of capitalism. By focusing on the most winnable reforms, we make value judgments about which sections of the working class we care about supporting. So often, we have chosen to appease the most reactionary sections of the working class—the ones whose position in our caste system give them the most vested interest in reformism, and thus in capitalism and imperialism; the most reason to stay complacent. And we have done it at the cost of alienating the advanced sections of the working class, who now mobilize to the left of DSA readily and in huge numbers in the ongoing Palestine movement.

DSA espouses the idea of revolutionary reforms, reform campaigns that galvanize the working class into action and organization, teaches people they have a world to win, and brings them into socialism and DSA as the path toward winning it. But we must be equally aware of what kind of consciousness these reformist slogans instill into people. In what ways are we stoking class consciousness by setting them against the capitalist class? And in what ways are we stoking settler consciousness by teaching them how to carve out a better life for themselves without upsetting the global system of imperialism?

A Hostile Environment

DSA is not oblivious to its whiteness problem. Time and time again, the national organization and its chapters have attempted prescriptive solutions, creating committees and work plans aimed at “fixing” DSA’s demographics. The AfroSocialists and Socialists of Color Caucus and the Multiracial Organizing Committee were both chartered and went defunct at points over the years, and neither have been successful at effectively adjusting DSA’s state and demographics. Other options have been layered with tokenization or deference politics that avoid organizing development and political development of new comrades of color.

The streak of racism that runs through DSA is not a solely structural problem, and it cannot be tackled solely through internal reforms, nor by yelling with a bull-horn that DSA is “anti-racist” into a void of which no answer ever comes. The problem we face is deeply political. Much like so many of its predecessors—the white-dominated organizations littered through the history of the American left—DSA is hostile toward organizing around issues of racial solidarity. To understand how, and why, we can look at DSA’s failure to adequately or effectively respond to the two largest social movements of the past five years: the George Floyd protests, and the Palestine solidarity movement. The problems here are not that DSA completely failed to respond, or that the organization felt that we shouldn’t. Rather, it’s that the responses failed in several ways that, while years apart, remained consistent.

First: DSA held the mass movements at arm’s length. Even while DSA did participate in both, there was always reservation around full-throated support. We could talk about a Black man being murdered by the police and center his identity as a worker, but not the racial antagonisms at play. Palestinian liberation is a good idea in the abstract, but we should keep our distance from the people supporting it, not to mention those actually engaging in it. “How can I proclaim Israel is committing genocide without alienating my Zionist coworkers?” These were the questions DSA grappled with, entrenched political stances appealing to the sensibilities of the imaginary white worker, and to the white workers that make up most of DSA, against which BIPOC members had to fight a losing battle. This also left us crippled in our ability and willingness to form connections with organizations that did represent segments of the working class marginalized within DSA, the Black and Arab communities at the center of these movements. We couldn’t tell them we fully supported their liberation struggles. The interests of DSA’s base came first.

Second: DSA fell into old patterns of reformist solutions at the cost of other types of organizing. The impulse was to try and tackle problems in the way we knew how. Our first major response to October 7th was No Money for Massacres, a campaign to phonebank our senators, unsuccessfully begging them to stop perpetrating a genocide. The second was the Uncommitted campaign, which futilely hoped to pressure the Democratic party into reversing their pro-genocide stance. Our attempts at anti-policing organizing hardly fared better, with endless proposed legislation defanged, defeated, and rolled back without working to cohere the energy of mass movements into a radical and organized base that may have provided enough support to enact them. All this at the cost of exploring and experimenting with new forms of organizing, as DSA continued to underfund its mutual aid work and failed to learn to organize protests.

Third: DSA failed to commit to orienting toward popular social movements, and thus failed to bring in masses of people outside our pre-existing base. DSA deprioritized organizing around mass movements in favor of its usual organizing priorities—labor work, electoral work, legislative reforms. When faced with Zionist politicians, DSA decided it was more important to retain our political connections than to set standards of racial solidarity. Neither anti-policing work nor Palestine solidarity work ever became a Priority Campaign. Rather than respond to either of these two major political flashpoints and reorient organizational time, energy, and resources toward the newly radicalized and BIPOC-led masses looking for a political home, DSA held the line on its main priorities, and remained firmly oriented toward the interests of the white working class.

Decolonizing DSA

Settlers is not an organizing manual. It offers no easy answers to the problems it identifies. It’s left to us to sift through the history of DSA as it fits within the legacy of the US left and the country from which it was birthed, and to present our own approaches to reckoning with our country’s class composition that results from its settler-colonial nature.

We must cease our patronizing of the white working class. We cannot attribute their support of empire solely to propaganda and brainwashing but must understand that it, too, is rooted in their material conditions and class interest. We cannot trick a beneficiary settler class into supporting socialism by leading only with reforms popular among their narrow electorate, drawing them in by pretending that their marginally increased comfort is all we want.

Instead, the white majority of DSA must actively decenter itself and its own interests. This is a scary prospect: DSA has always been an organization people join primarily because of investment in and then disillusionment with our political establishment, membership growth corresponding more with the news cycle than our organizing projects. But building toward a revolutionary horizon must start with a full, and not partial, integration of all those with grievances against capitalism. By centering a settler politic we shear off a huge potential section of those whose class position is most oppositional to capitalism; those who have, by firsthand experience at the gunpoint of the US imperialist state, most developed their understanding of and opposition to the current order.

If we are to break out of the feedback loop of our white membership and base, we must take seriously the task of identifying the base our campaigns and organizing work are activating and recruiting from, who we are trying to appeal to, and move our focus over to projects that directly benefit the strata of BIPOC workers most under the boot of capitalism. This may mean abandoning some of the campaigns that have brought DSA this far, but brought us no further than the failed white-centered social democratic projects of the US’s past. If we are unlucky enough for another George Floyd or October 7th, we must craft our response with clear eyes that our priority is not to maintain the legitimacy of our electoral project, or to protect our potential policy victories, but instead to offer an understanding of capitalism, imperialism, and the global caste system of empire; and to offer an organizing home to all those seeking it and be a vehicle for the coordination of their activity.

If we are to raise class consciousness while suppressing settler consciousness, we cannot acquiesce to settler consciousness by settling for reforms. We cannot meet our white middle-class base where they’re at—hoping for the crumbs of imperial superprofits. We cannot tail the social strata of our existing membership, guiding DSA’s politics with a message tailored to them. This will leave us always limited to reformism, appealing to the most reactionary sections of the US working class; and by centering them, allowing DSA’s reformist and reactionary elements to dominate over its revolutionary aspects. We must instead unapologetically lead with a vision of anti-imperialism and decolonization. Socialism is a project of changing minds and coordinating our grievances against imperial capitalism; of creating majorities, not finding them.

Further Discussion

If you're interested in discussing this piece with other DSA members, head on over to the DSA Discussion Forum at discussion.dsausa.org.

The forums are open to all DSA members in good standing. If you're not a DSA member in good standing, sign up or renew your dues at act.dsausa.org/donate/membership.